By Mike HensonBBC Sport

Last updated on .From the section Sport

This feature was originally published in July and is being repromoted as part of our Black History Month series.

Ezekiel Mitchell pauses for a moment when asked to describe his toughest opponent.

He eventually opts for a nine-year-old. Admittedly one with a steely glare backed up by 121 stones of slabbed muscle.

“I would have to say Sweet Pro’s Bruiser,” he tells BBC Sport. “The power and sheer athleticism of him, he’s able to do things some bulls just can’t. If you’re just a millisecond too late, he’s put you on the ground.”

There is no choreography to their dance. Mitchell relies on deep-seated muscle memory and pure instinct to counter the steps of the wheeling, convulsing bull below.

“Once you get in the bucking chute, your subconscious mind clicks in and your conscious mind clicks out,” he says.

“It’s taking complete and utter chaos and trying to control it for eight seconds. It’s unreal.”

Mitchell, from Rockdale, Texas, is the only black American in pro bull-riding’s top 50 ranked riders.

At 23 years old, he’s already encountered forces less obvious, but no less powerful than Sweet Pro’s Bruiser in his life and career so far.

The odds didn’t use to be so stark.

When the American Civil War ended in 1865, many of Texas’ slave-owning settlers returned home from fighting for the Confederacy to be confronted by a newly freed black workforce, knowledgeable in ranching.

Modern barbed wire, which made containing cattle easier and cheaper, had yet to be invented and the major railroads that transported them large distances had yet to stretch as far as Texas.

The master-slave relationship morphed into one of employer-employee as black men, still struggling to find work in many other sectors, were hired to care and transport herds.

Soon after, it is estimated that one in four cowboys in the West was black. That ratio was significantly watered down when the era was recreated in popular culture, however.

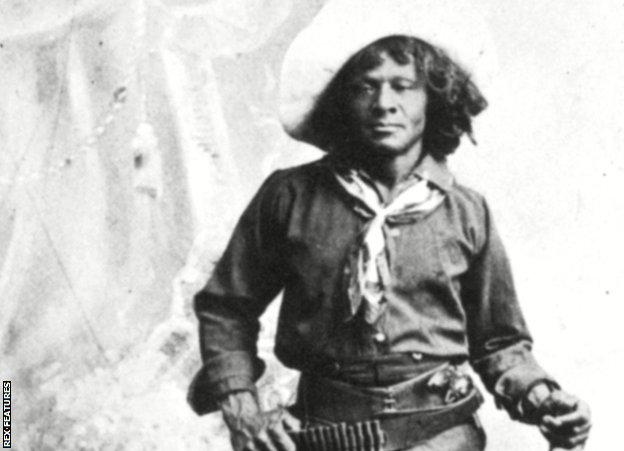

There are some exceptions. Bill Pickett was a celebrated black rodeo performer in the early 20th century. Historian William Katz wrote about the history of the black cowboy in the 1970s. In the 1980s, American novelist Larry McMurty won a Pulitzer for Lonesome Dove, which featured a black cowboy character.

But in the American imagination, a cowboy was a white man.

Are rodeos a form of culture or cruelty?

To say that animal welfare organisations and rodeos do not see eye-to-eye is an understatement. For one side, it is a cruel act of animal abuse. For the other, it is an entertaining and competitive sports event that is part of their culture.

“We grew up with the idea of a white cowboy, the idea that a cowboy would look like John Wayne or a the guy in the Marlboro cigarette ads,” explains Walter Thompson Hernandez, journalist and author of The Compton Cowboys.

“The image of black men and women on horses was not available as part of popular culture.”

Rodeo – which turns the tasks of the old ranch hands into competition – did not buck the trend. Despite the success of pioneering black rider Myrtis Dightman, who became the first black man to compete in the National Finals in 1964, a ‘colour barrier’, whether overtly stated or implicit, kept black competitors out of some events as late as the 1980s.

Now they are included. How welcome they are though, depends on who you speak to.

Neil Holmes grew up a couple of hours’ drive from Mitchell in Cleveland, Texas. He was captivated by bull-riding after attending an annual rodeo, held after church each Easter in the town. Despite only getting on board a bull at the relatively late age of 17, he reached the top 40 of the elite-level Professional Bull Riders tour before retiring in 2018.

“There is always that elephant in the room, when you are different it is obvious, especially in that sport,” he says.

“Among the riders the camaraderie is always great, but sometimes you go into these smaller towns and everyone doesn’t feel the same way.

“I have had fans say some obscene things or make obscene gestures. A lot of times we have to stay in that same town and I have always got that look…

“There’ve have been occasions that there has been a fist fight at the bar just because I’m a black guy with a cowboy hat on. It is rare, especially as times change, but I hope that we set a good enough example by how we carry ourselves that it outweighs whatever hatred they have in their hearts.”

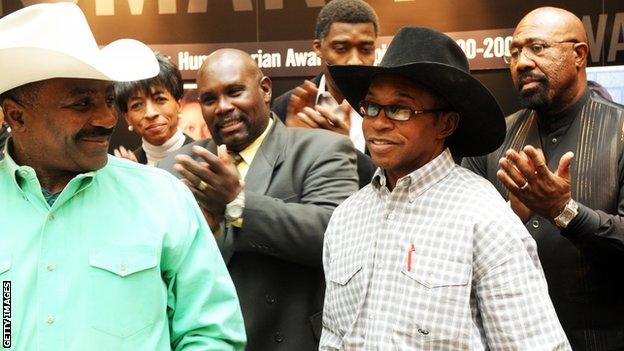

Both Mitchell and Holmes have followed in the footsteps of Charles Sampson. In 1982, a 5ft 4in 25-year-old, he emerged from Los Angeles’ notorious south side to become the first black world champion bull-rider.

Occasionally referred to as bull-riding’s own Jackie Robinson, Sampson takes the long view, setting his experiences in the context of the prejudice suffered by the ground-breaking baseball star and other earlier black sporting pioneers.

“America still has history of racism – everyone goes through it in their own manner,” he tells BBC Sport.

“My emphasis in what I went through is positive. The racism in the 1920s, 1930s or 1940s was not a type that I had to deal with.

“Did white people do anything to me? Maybe they did and I didn’t look at it that way. Maybe I overlooked it or didn’t understand it.

“But no-one stopped me, no-one belittled me, no-one told me that just because I was black I wasn’t equal to white people.”

The fear is that they may not have had to.

The bull may not care about the colour of the man on its back, but those who open the bucking chute and supply the livestock are also gatekeepers for the sport’s human participants.

“Bull riding is not like baseball, football or basketball,” adds Sampson. “You can pick up a stick and rock and swing and hit, you can throw a football to anybody, or go anywhere, pick up a basketball and shoot it.

“Rodeo is different. You have to seek out places to ride bulls and hopefully the people who own them are not trying to overmatch you and discourage you.”

If access is the first obstacle for the novice, subjectivity can be the one that confronts black riders once they make it into a competitive rodeo ring.

Riders are up against the clock – attempting to stay on top of the bull for eight seconds – but also a panel of judges. They are marked on how hard the bull bucked and how well they countered.

“There is always that room for error,” adds Holmes.

“I feel I have got the short end of the stick from some of those old-school judges, which is kind of sad. If they have to choose me or the all-American white boy, no question, I don’t get that advantage.”

Harder to measure than points or prize money is how a lack of black riders stunts the sport’s growth in those communities, perpetuating a sense that bull-riding is not for them. It is one that even Mitchell struggles to shake.

“It did give me a sense of comfort, the likes of Charlie and Neil being there and having achieved what they achieved,” he says.

He recalls meeting “small-town old-timer people who are still set in their ways” on the lower-level circuit.

“There is a bit of prejudice there,” he adds. “Since I have always wanted to be a cowboy I grew to ignore a lot of the hateful comments.

“But on the Professional Bull-Riders tour as a professional athlete I have really not felt any prejudice. I commend the fans and the PBR for making me feel welcome. There are some times when you feel like you don’t belong, but I wouldn’t say that the prejudice lingers.”

Mitchell does not intend to linger at the top level either.

Rodeo is an inherently risky pastime. Careers are short, injuries often horrific. Mitchell recalls his ear being ripped by a bull’s hoof: “If it had been an inch over it probably would have stomped my head into the ground and killed me.”

His career template is unexpected. He cites WWE wrestler-turned-Hollywood A-lister Dwayne ‘The Rock’ Johnson as his crossover inspiration for turning a specialist sporting career into a mainstream success.

“He transformed his life into something totally different. That is what I want for myself,” Mitchell adds.

“I want to show people that you can do whatever you want to no matter the circumstance you come from or what colour you are as long as you have drive and determination.”

The brand building for Mitchell’s next move has already begun. Behind him as we speak a multi-screen display beams out his personal bull-horned logo. More than 170,000 followers on TikTok watch him goofing, singing and shooting pool.

But it is his day job, mounted on a bull or horse, that draws the most attention.

On 2 June, a Black Lives Matter protest was organised for downtown Houston in reaction to the death of 46-year-old George Floyd in police custody eight days earlier in Minneapolis.

While displays of solidarity have been held in all 50 states, images from Houston went viral thanks to the arrival of tens of protestors on horseback, fist aloft, trotting down the city’s main street.

“Just seeing black cowboys is in of itself a form of protest,” says Thompson Hernandez.

“Being a black cowboy demonstrates against a part of history that has been erased and restores part of the narrative that not a lot of people grow up learning in schools or books.”

Images of the mounted protestors were shared on social media by rapper Lil Nas X – whose Old Town Road hit has brought black cowboy culture to prominence in music. Corporate brands like Wrangler and Guinness have borrowed the power of the imagery to push their products. Fashion magazines hire them to add edge to shoots.

“It is interesting because every 15-20 years there is a big black cowboy cultural movement,” adds Thompson Hernandez. “You see Wild Wild West (1999), Django Unchained (2012) even Blazing Saddles (1974) – it is almost like Hollywood and popular culture forgets about black cowboys, until they don’t.”

Holmes puts it more succinctly.

“Those rodeo judges with the old-school mentality may not like us, but the kids love us and everything we stand for,” he says.

“If we don’t do it – if we don’t ride those bulls or no black guys are seen on horseback – eventually that history will fade away so we have a responsibility as minorities and cowboys to uphold that legacy and make sure it lives on forever. “

Mitchell, who used to ride his horse through drive-thrus back home in his small hometown of Rockdale, knows the power of the symbol he embodies.

“It’s not as common to the outside world, it definitely does draw attention,” he concludes.

“The image of having a black cowboy skews some of the stereotypes that exist around the black community. But I feel my personality and ability to get the job done also enhances that attention.

“That’s what it’s all about I guess. You wouldn’t be speaking to somebody who wasn’t doing anything.”

As the most prominent black cowboy in the USA, Mitchell’s mere existence is doing plenty of things.